The Ties That Bind

By Robyn Murray

UNK, UNMC Work to Bring More Medical Professionals to Rural Nebraska

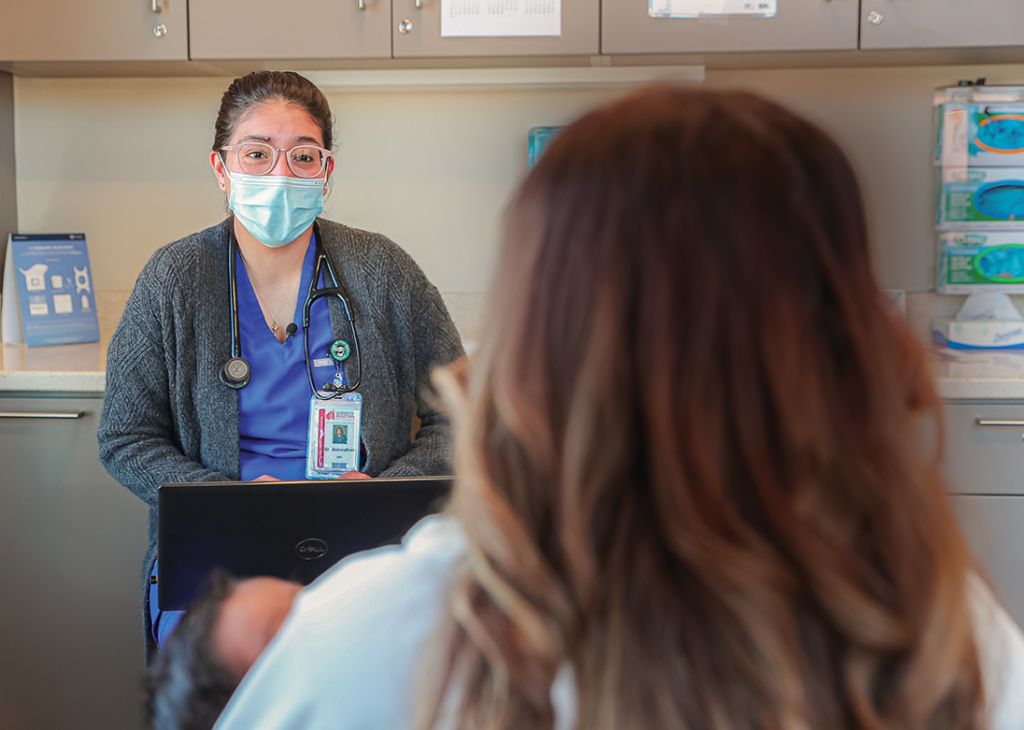

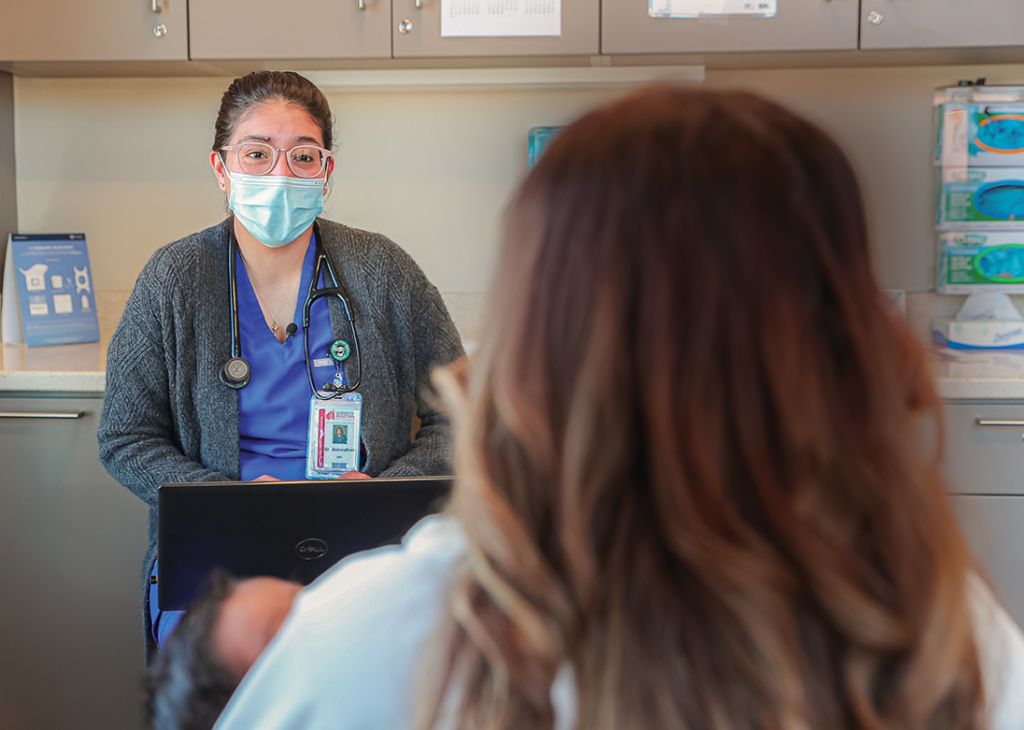

When Sandra Bresnahan, M.D., was a child, she often came with her parents to doctor appointments. Her parents were immigrants from Mexico and didn’t speak much English. So they needed her to explain their symptoms to the doctor and translate what was told to them.

“As a young kid, that’s kind of hard,” said Bresnahan, who now works as a family physician at Lexington Regional Health Center. “Kids should be sheltered from having to do that or knowing what the health issues of their parents are, because it creates anxiety that they don’t need growing up.”

Bresnahan is a graduate of the University of Nebraska at Kearney and the University of Nebraska Medical Center. She grew up in Lexington, a town of about 10,000 people in central Nebraska. As with many small Nebraska towns, Lexington is becoming more diverse. The town’s Hispanic population has boomed in recent years as immigrants have been drawn to work at local meatpacking plants. That means more and more Lexington patients need physicians who can speak Spanish.

“We tend to relate to people that are similar to us,” Bresnahan said. “For somebody, if they have a doctor that speaks Spanish, that understands their cultural beliefs, it does make them feel a little bit more understood or safer in that environment.”

Getting Bresnahan to practice as a physician in her home community was a coup for Lexington. Lexington Regional Health has kept tabs on Bresnahan since high school, when they first learned she was interested in medicine.

“[We said,] ‘Hey, we definitely want to follow this person and see where things go,’” said Francisca Acosta-Carlson, M.D., the chief medical officer at Lexington Regional Health Center. “And when she ended up getting into medical school, there was definitely a bigger push for recruiting her.”

But Lexington’s need for Spanish-speaking physicians is just one piece of a far more complex puzzle. Rural towns across Nebraska are facing dire shortages of all types of medical professionals. According to a 2020 study by the Nebraska Area Health Education Center Program and UNMC, 14 of Nebraska’s 93 counties do not have a primary care physician; 16 counties have no dentists; 17 have no pharmacists; and the north-central region of the state has virtually no occupational therapists, speech-language pathologists or medical nutrition therapists. The study said Nebraska’s population shifts are exacerbating the problem, and the result is growing inequity and unmet health care needs.

Part of the challenge is it can be difficult to convince people to move to a small town — particularly physicians and other medical professionals who may be eyeing big-city opportunities and need to ensure they can pay back hefty medical school tuition loans. But UNK and UNMC are committed to changing the status quo.

In 2010, the two teamed up to establish the Kearney Health Opportunities Program. KHOP offers students interested in health care careers a full-tuition scholarship to attend UNK and guaranteed admission to UNMC if all requirements are met. Currently, more than 100 UNK students are receiving their pre-professional training in one of 10 medical fields. In 2015, the UNMC-UNK Health Sciences Education Complex opened its doors, offering start-to-finish programs in nursing and allied health professions on campus in Kearney. These programs have proven success based on the 50/50 maxim: 50% of graduates find a job within 50 miles of where they completed their residencies.

“If we want health professionals to practice in rural communities, we have to train them in rural communities,” said Nicole Carritt, MPH, director of Rural Health Initiatives at UNMC.

The benefit of keeping medical professionals in rural communities is multifold. Not only do small towns need the services those practitioners provide, but they also need their economic impact.

“An advanced practice registered nurse contributes about $250,000 annually to a local economy,” Carritt said. “And when we’re talking about a physician, we’re talking about $1.3 million annually. So they’re certainly important in increasing access to care and the health of the population, but also to the economic viability of our rural communities.”

Highly educated graduates also become leaders in their communities, taking on volunteer roles or sitting on boards. Andy Craig, M.D., is a family physician at Kearney County Health Services in Minden. He grew up in Minden and said he always wanted to be a physician.

“We had a family physician I really looked up to,” Craig said. “So even as a child, I knew that I wanted to be a physician.”

Craig got his bachelor’s degree at UNK and enrolled in KHOP in one of the program’s first cohorts of students. He said his experience there helped him succeed both in Kearney and Omaha, where he completed medical school and his residency at UNMC.

“Looking back on that experience, it was so positive,” he said. “When your aspirations are to do something [that requires another four years of coursework], you have people that are so supportive, people that want to push you to do your best, and people that care about your success.”

It also helped that his younger brother, Cade, was following in his footsteps.

“It’s not something I head-locked him about or anything,” Craig joked, “but I always thought it would be awesome to work together.”

Cade Craig, M.D., attended UNK four years after his older brother and followed him to medical school in Omaha after receiving his bachelor’s degree. He said when his brother started talking about going into medicine in seventh grade, the idea just stuck, and now he feels fortunate they get to work together in the same clinic in their hometown.

“Medicine is kind of a team sport nowadays,” Cade Craig said. “Especially with complex cases, having colleagues that you trust and value to discuss the findings and to see what their thoughts are based on that data is pivotal to being able to really take good care of people.”

Cade Craig said practicing in a rural community has many benefits, including the variety general physicians experience as opposed to specialists. Andy Craig agreed and said the relationships physicians build with their patients are what make the work fun.

“Building those relationships among generations of families is really a joy,” he said. “And it really does provide a more holistic opportunity to care for the patient because you know things that are going on in their lives — their stressors, their joys. It allows you to care for the patient in a better way because you know what’s going on behind the scenes.”

The Craigs are living out their dream, and they wouldn’t have it any other way. But their careers might not have gone the way they did. They each spent seven years studying and completing their residencies in Omaha, and as Carritt said, “life happens” when people move away. Sometimes it’s tough to come back.

“Once you make that step, sometimes it’s really difficult to go back,” Carritt said. “You’re exposed to new things; you meet folks. The reality is, the closer that we can keep them to home and where we want them to practice, the more likely they are to stay in our rural communities.”

UNK and UNMC work hard to ensure the ties that bind students to their rural communities are nurtured throughout their educational careers, whether they are in Kearney or Omaha, said Peggy Abels, director of health sciences at UNK. KHOP students are grouped together in learning communities; they live together and form connections that last beyond graduation, and UNMC provides opportunities for rural rotations whenever possible.

But not only can studying in Omaha draw students away from their rural roots, the prospect of moving to a big city can also be a deal breaker for some students considering health care careers.

“Forty percent of our students are first-generation students,” Abels said. “For a lot of them, to move to a city with several stoplights is kind of a monumental move when they start college.”

Medical school is also one of the most challenging educational experiences, and leaving a support network can make it that much more daunting.

Bresnahan, who was also a KHOP student, said she would have loved the opportunity to attend medical school within a short driving distance from home.

“Medical school is really overwhelming,” she said. “I would try to come back as much as I could. But with how much work there is, it was really hard to even come back on the weekends. So it would have been nice to just be close to home.”

UNK and UNMC are working to expand their collaboration to create more opportunities for future physicians, pharmacists, public health professionals and others to complete their studies closer to home. Those efforts were supported tremendously when Nebraska lawmakers approved $60 million during the spring legislative session to help fund the UNK-UNMC Rural Health Education Building, which will cost $85 million in total. But the work is not done yet. Private support will be crucial to raise an additional $25 million needed to complete the project, and collaboration will be key to its success.

“There’s not one piece of that puzzle that’s more important than the other,” Carritt said. “It’s not the resources or the community or the academic system. We all have to kind of work in concert to problem-solve and keep our finger on the pulse of what’s happening.”