UNO Fund Student Scholarship Stories – Reagan Folda

As a student in the Sign Language Interpreting program at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, Reagan Folda understands the importance of a clear and

UNK has a proud tradition of excellence and support when it comes to Loper Athletics and enjoy great success in all sports.

Find specific areas to support within your college, department, program or area of interest.

Looking for ways to make the greatest impact to the University of Nebraska at Kearney and its students? Here are some great options.

No matter your circumstances. No matter your age or financial situation. If leaving a legacy is important to you, we can help through planned giving.

UNK AA has been working since 1906 to promote communication and interaction among more than 40,000 alumni, students, faculty, administrators and friends of the University of Nebraska at Kearney.

Husker athletic programs at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln are a source of pride for alumni and Nebraskans throughout the state and around the world.

Find specific areas to support within your college, department, program or area of interest.

Looking for ways to make the greatest impact to the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and its students? Here are some great options.

No matter your circumstances. No matter your age or financial situation. If leaving a legacy is important to you, we can help through planned giving.

NAA is a nonprofit organization that connects alumni with Dear Old Nebraska U, and with each other, for the betterment of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

There are many ways to give including employer matching, payroll giving, donor advised funds, tangible property, grain, stocks and more.

Find specific areas to support within your college, department, program or area of interest.

Looking for ways to make the greatest impact to the University of Nebraska Medical Center and its students? Here are some great options.

No matter your circumstances. No matter your age or financial situation. If leaving a legacy is important to you, we can help through planned giving.

The mission of the UNMC Alumni Relations Office is to serve and engage with learners and graduates through effective communications, the formation of meaningful relationships, and opportunities to invest in the advancement of the university through gifts of time, talent, and treasure.

Our athletes are competing at the Division I level in collegiate sports, not only enhance the visibility of UNO, but also to provide great benefits to all of Omaha.

Find specific areas to support within your college, department, program or area of interest.

Looking for ways to make the greatest impact to the University of Nebraska at Omaha and its students? Here are some great options.

No matter your circumstances. No matter your age or financial situation. If leaving a legacy is important to you, we can help through planned giving.

UNO AA is an organization focused on strengthening connections with more than 100,000 UNO alumni, students and friends from all over the world.

Nebraska Medicine and its research and education partner, the University of Nebraska Medical Center, share the same mission: to lead the world in transforming lives to create a healthy future for all individuals and communities through premier educational programs, innovative research and extraordinary patient care.

These funds support innovative initiatives at Nebraska Medicine that allow the academic health network to take advantage of emerging opportunities.

There are many ways to give including employer matching, payroll giving, donor advised funds, tangible property, grain, stocks and more.

Looking for ways to make the greatest impact at Nebraska Medicine? Here are some great options.

No matter your circumstances. No matter your age or financial situation. If leaving a legacy is important to you, we can help through planned giving.

The Nebraska College of Technical Agriculture is devoted to a statewide mission of preparing students for successful careers in agriculture, veterinary technology and related industries. The college provides open access to innovative technical education resulting in associate degrees, certificates and other credentials.

Members of the NCTA Aggie Alumni Association support the Curtis Aggie NCTA Scholarship Fund.

Looking for ways to make the greatest impact at NCTA? Here are some great options.

No matter your circumstances. No matter your age or financial situation. If leaving a legacy is important to you, we can help through planned giving.

There are many ways to give including employer matching, payroll giving, donor advised funds, tangible property, grain, stocks and more.

The mission of the Buffett Early Childhood Institute at the University of Nebraska is to transform the lives of young children by improving their learning and development.

Every day, nearly a billion people in the world do not have enough safe and nutritious food to lead healthy and active lives. Many of them also lack access to enough clean water to meet their needs. By 2050, our global food demand will double to meet the needs of nearly 10 billion people, making water and food security one of the most urgent global challenges of our time.

Looking for ways to make the greatest impact? Here are some great options.

No matter your circumstances. No matter your age or financial situation. If leaving a legacy is important to you, we can help through planned giving.

Your giving to this area enables the president’s office to quickly direct resources to various university projects and areas across the system as needs arise.

The greatest needs of the University of Nebraska at Kearney. Gifts through the UNK Fund let you make a bigger difference on campus, your college and students.

The greatest needs of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Gifts through the N Fund let you make a bigger difference on campus, your college and students.

The greatest needs of the University of Nebraska Medical Center. Gifts through the Innovation Funds let you make a bigger difference on campus, your college and students.

The greatest needs of the University of Nebraska-Omaha. Gifts through the UNO Fund let you make a bigger difference on campus, your college and students.

Add your voice and your support to see the power of the crowd in action.

UNK has a proud tradition of excellence and support when it comes to Loper Athletics and enjoy great success in all sports.

Find specific areas to support within your college, department, program or area of interest.

Looking for ways to make the greatest impact to the University of Nebraska at Kearney and its students? Here are some great options.

No matter your circumstances. No matter your age or financial situation. If leaving a legacy is important to you, we can help through planned giving.

UNK AA has been working since 1906 to promote communication and interaction among more than 40,000 alumni, students, faculty, administrators and friends of the University of Nebraska at Kearney.

Husker athletic programs at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln are a source of pride for alumni and Nebraskans throughout the state and around the world.

Find specific areas to support within your college, department, program or area of interest.

Looking for ways to make the greatest impact to the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and its students? Here are some great options.

No matter your circumstances. No matter your age or financial situation. If leaving a legacy is important to you, we can help through planned giving.

NAA is a nonprofit organization that connects alumni with Dear Old Nebraska U, and with each other, for the betterment of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

There are many ways to give including employer matching, payroll giving, donor advised funds, tangible property, grain, stocks and more.

Find specific areas to support within your college, department, program or area of interest.

Looking for ways to make the greatest impact to the University of Nebraska Medical Center and its students? Here are some great options.

No matter your circumstances. No matter your age or financial situation. If leaving a legacy is important to you, we can help through planned giving.

The mission of the UNMC Alumni Relations Office is to serve and engage with learners and graduates through effective communications, the formation of meaningful relationships, and opportunities to invest in the advancement of the university through gifts of time, talent, and treasure.

Our athletes are competing at the Division I level in collegiate sports, not only enhance the visibility of UNO, but also to provide great benefits to all of Omaha.

Find specific areas to support within your college, department, program or area of interest.

Looking for ways to make the greatest impact to the University of Nebraska at Omaha and its students? Here are some great options.

No matter your circumstances. No matter your age or financial situation. If leaving a legacy is important to you, we can help through planned giving.

UNO AA is an organization focused on strengthening connections with more than 100,000 UNO alumni, students and friends from all over the world.

Nebraska Medicine and its research and education partner, the University of Nebraska Medical Center, share the same mission: to lead the world in transforming lives to create a healthy future for all individuals and communities through premier educational programs, innovative research and extraordinary patient care.

These funds support innovative initiatives at Nebraska Medicine that allow the academic health network to take advantage of emerging opportunities.

There are many ways to give including employer matching, payroll giving, donor advised funds, tangible property, grain, stocks and more.

Looking for ways to make the greatest impact at Nebraska Medicine? Here are some great options.

No matter your circumstances. No matter your age or financial situation. If leaving a legacy is important to you, we can help through planned giving.

The Nebraska College of Technical Agriculture is devoted to a statewide mission of preparing students for successful careers in agriculture, veterinary technology and related industries. The college provides open access to innovative technical education resulting in associate degrees, certificates and other credentials.

Members of the NCTA Aggie Alumni Association support the Curtis Aggie NCTA Scholarship Fund.

Looking for ways to make the greatest impact at NCTA? Here are some great options.

No matter your circumstances. No matter your age or financial situation. If leaving a legacy is important to you, we can help through planned giving.

There are many ways to give including employer matching, payroll giving, donor advised funds, tangible property, grain, stocks and more.

The mission of the Buffett Early Childhood Institute at the University of Nebraska is to transform the lives of young children by improving their learning and development.

Every day, nearly a billion people in the world do not have enough safe and nutritious food to lead healthy and active lives. Many of them also lack access to enough clean water to meet their needs. By 2050, our global food demand will double to meet the needs of nearly 10 billion people, making water and food security one of the most urgent global challenges of our time.

Looking for ways to make the greatest impact? Here are some great options.

No matter your circumstances. No matter your age or financial situation. If leaving a legacy is important to you, we can help through planned giving.

Your giving to this area enables the president’s office to quickly direct resources to various university projects and areas across the system as needs arise.

The greatest needs of the University of Nebraska at Kearney. Gifts through the UNK Fund let you make a bigger difference on campus, your college and students.

The greatest needs of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Gifts through the N Fund let you make a bigger difference on campus, your college and students.

The greatest needs of the University of Nebraska Medical Center. Gifts through the Innovation Funds let you make a bigger difference on campus, your college and students.

The greatest needs of the University of Nebraska-Omaha. Gifts through the UNO Fund let you make a bigger difference on campus, your college and students.

Add your voice and your support to see the power of the crowd in action.

Kyle Luthans, Becker Professor of Business at UNK, is a leader in the area of positive psychology in the workplace and management education. He chairs the business management department.

Home > Archives for October 9, 2019

Can a UNK business professor practice what he preaches after his wife is diagnosed with cancer?

Kyle Luthans, B.S., M.A., and Ph.D., from the University of Nebraska–Lincoln and the Becker Professor of Business at the University of Nebraska at Kearney, is a leading researcher in his area of positive psychology in the workplace and management education.

He’s an expert in seeing the very real science and empirical evidence behind the concept of positive psychological capital, or PsyCap for short. Briefly, PsyCap is the recognition that a person’s key psychological resources can be leveraged for success for improved outcomes.

For example, PsyCap has been linked in prior research with positive workplace outcomes such as lower employee turnover, high-rated work performance, higher employee commitment and satisfaction, entrepreneurial success, and leadership effectiveness in a variety of industries such as banking, health care, transportation and manufacturing.

A growing body of PsyCap research, he says, suggests that workers perform better when they possess the psychological resources of the HERO within:

Hope. (The will and the way for reaching goals.)

Efficacy. (Self-confidence.)

Resilience. (The ability to bounce back, and beyond, from setbacks.)

Optimism. (An expectation of future success.)

“I’ve taken my research in another direction,” Luthans says, “and I’m looking at the impact of academic PsyCap on important educational outcomes like student engagement and academic performance.”

A fascinating thing about PsyCap, he says, is that the research also suggests it’s malleable. In other words, it can be changed and developed within individuals. That’s why he loves to teach this concept to his students. He knows PsyCap-boosting strategies could help them not only in the classroom, but also in their personal lives and future careers.

Sometimes, Luthans shares a story from his own life with his students, a story that shows how PsyCap helped him cope, and find hope, about seven years ago, when a phone call shattered his life. The call came in 2012. It was the doctor for his wife, Dina.

Her biopsy results were in.

I’m sorry …

She had pancreatic cancer.

“It really was just a bolt out of the blue,” Luthans says. “She was just the picture of health. She had a healthy diet. She never smoked. She exercised. She did all the right things.”

She taught me to have a little more compassion and a little more empathy for others, to realize that a lot of people go through difficult times.

- Kyle Luthans

They’d met over 20 years ago in study hall at Lincoln East High School. She was on the student council, Singers, and the Apollonaires dance team. Their first date was the prom: Enchantment Under the Sea. She was blond and beautiful in her black dress.

After receiving her B.A. and M.A. from UNL, she became an elementary teacher, then became a stay-at-home mom and substitute teacher while their two kids were little. She loved to watch Emma dance and Will play sports. She was their rock.

Their hero.

“She taught me to have a little more compassion and a little more empathy for others,” Luthans says, “to realize that a lot of people go through difficult times.”

The diagnosis overwhelmed him at first. He was depressed and full of worry and doubt.

“I think I was even crying in my dreams,” he says. “And I’d wake up stressed and wondering: How am I going to take on this day?”

But it soon dawned on him that maybe he should practice what he preached and find strength in the strategies he knew worked so well in the workforce.

He knew, from his PsyCap research, that building good relationships on the job was important, so at home he tried to stay in the moment with Dina and their kids and maintain their close bond. He kept coaching Will’s basketball team, even though at first he’d wanted to quit. He kept up with friendships and fishing trips.

In a way, he faked it until he could make it.

“Traditionally, we think that if we work hard and are successful, we will feel positive,” he says. “But, we should turn it around and say that positivity — and having the right mindset — leads to success.”

He tried to keep Dina’s spirits high. One day, for example, when she was feeling low, he played a song for her with the volume high.

Pearl Jam’s “Alive.”

Oh I, oh, I’m still alive

Hey, hey, I, oh, I’m still alive

Hey I, oh, I’m still alive, yeah oh

He knew, from his research, that healthy living was important, so he made sure the family kept eating right and exercising. He and Dina kept going on long nature walks in the park beyond their backyard gate.

He continued his normal load of classes and research at UNK. He earned the Becker professorship, which made Dina proud.

He knew that gratitude was important, so every night, as he lay in bed, he made himself think of three great things that had happened that day.

It all worked.

He felt alive again. And Dina lived longer than expected.

“I definitely think Dina beat the odds by battling the disease over three years,” he says. “A big part of that, I think, was the care she received at UNMC. But then again, I go back to PsyCap — she had such a positive attitude and the mindset that she was going to beat the disease or extend the fight as long as possible.

“And, interestingly, those PsyCap strategies helped me support her through this and also helped with my own psychological well-being.”

He’s grateful for his job at UNK. One of the things he likes the most about being a professor, he says, is the impact he can have on students.

“Probably the greatest satisfaction I have is when I see my students graduate and I see the successful careers they’re having,” he says. “A lot of our graduates go on to successful business careers, and we even have placement data to suggest that a lot of them stay right here in Nebraska and have a big impact on our region and in our state and within our local community in the central Nebraska area.”

And a lot of them, he says, are affecting the lives of the people around them in positive ways. At work. At home. …

Like heroes.

As a student in the Sign Language Interpreting program at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, Reagan Folda understands the importance of a clear and

As a full-time social worker, Matthew Beckmann works every day to assist those who most need support. In the course of working on behalf of

“I think education is very important, and all of these young people need to have a career. That’s our future. The young people become educated and good citizens.”

Radiel Cardentey-Uranga graduated from UNMC in May with high distinction.

Home > Archives for October 9, 2019

UNMC graduate overcomes obstacles to embrace opportunities.

His mom made him look at her hands.

They were swollen, again.

She reminded him how much they ached, day after day, from her job packaging meat at a factory in Columbus, Nebraska.

“She told me, ‘This is the reason you have to go to college. You should get an education. It’s going to help you in the future,’” Radiel Cardentey-Uranga, a recent graduate of the University of Nebraska Medical Center, says.

A few weeks before his graduation, Cardentey-Uranga turned 23. He dreams of a career in radiography, using his hands to help people. He sees that career within his reach now — and maybe, down the road, he’ll become an M.D. or Ph.D. or a physician’s assistant — and he sees himself giving back to the community one day. He knows it’s all thanks to his parents and teachers and all the people who extended their hands to him along the way, pulled him up to where he is today.

To who he is today:

A hardworking, recent college graduate, the first in his family to attend college …

A grateful recipient of two UNMC scholarships: the Charles R. O’Malley Scholarship and the Hermene K. Ferris Scholarship, generous gifts from people who don’t even know him …

A proud citizen of the United States, as of last summer …

And a proud narrator of a very unlikely story. One he can hardly believe himself, he says, as he tells it over the phone from his home in Columbus, Nebraska.

She told me, ‘This is the reason you have to go to college. You should get an education. It’s going to help you in the future.'

- Radiel Cardentey-Uranga

His story began in Cuba. It began even before he was born, when his hardworking dad was thrown in jail for two years for speaking out against the government.

“He just wasn’t in favor of the tyranny or the dictatorship they had,” Cardentey-Uranga says. “He was publicly speaking the truth that the government doesn’t want you to tell.”

When his dad got out of jail, he tried to go back to working in construction. He had a good reputation working with his hands, in masonry. But police were always giving him citations, harassing him, ticketing him. Cardentey-Uranga’s family eventually applied to come to the United States as refugees and was accepted.

Cardentey-Uranga was 16 when he came over with his parents and older brother. After some time in Washington state, his parents split up. Cardentey-Uranga and his mom came to Columbus, where his mom, who had used her hands doing hair and nails out of her home back in Cuba, took on that tough factory job.

Cardentey-Uranga could barely speak or understand English, so he wasn’t much of a student at first at Columbus High School. He’d dropped out of school in Cuba in ninth grade because of his family’s fears that if he kept going, he’d get taken away and thrown into military service, which in Cuba is mandatory.

He struggled because of those years of school he missed, especially in math and physics.

“Basically,” he says, “I had to learn it all from scratch.”

He joined the high school soccer team, which helped because some of the players spoke Spanish. He took a weekend job at an animal shelter, and that helped him learn English. He started to fit in.

A few teachers took him under their wings, encouraged him to try for higher education and pointed him in the direction of Central Community College.

But he didn’t think he was college material. He figured he’d just find a factory job, too, when he graduated.

That’s when his mom made him look at her swollen hands.

“She said, ‘This is the reason you have to go through school. I’m making the sacrifice for you. You should take a chance at the opportunity,’” Cardentey-Uranga says.

He did. He started asking questions about the path to higher education. He took the ACT but scored poorly at first. He started at the community college, way behind the other students. He took evening classes, summer classes. He got to know one of the Spanish instructors there, and she suggested he consider a career in radiography. She told him UNMC had a radiography program he could take right there in Columbus.

Radiography?

He researched it, loved what he saw and applied to the program at UNMC, which has a partnership with a hospital in Columbus. As part of the application process, he was required to do a three-day job-shadowing stint to make sure he really wanted to work in that field.

“I liked the job,” Cardentey-Uranga says. “I felt like it really fit me because I’m using my hands constantly, in different ways. You use the computer sometimes; you’re constantly running around and moving. I like to move. And you get to work with people from all different backgrounds and cultures.”

He applied for scholarships. Then he forgot he’d done so, until one day when he opened an email telling him he’d received the O’Malley and Ferris scholarships. The O’Malley Scholarship was created by the largest gift to benefit UNMC’s College of Allied Health Professions students to date. Besides allowing the college to endow funds for a cohort of “O’Malley Scholars,” the gift provides an additional $500,000 if matched by other allied health donors through 2022. The matching arrangement allows benefactors to endow their own named scholarships, with the benefit of doubling their gift.

“When I got it,” he says. “I got an email telling me and when I read it, I was like, OK, this can’t be real. They probably sent it to the wrong person!”

He laughs.

“But I guess someone realized that I was really working hard to achieve good academic performance. And I got the scholarships, and they truly make a difference. The money helps out with school. But what also really impacts me is the fact that it makes me know there are people out there who are actually invested in your future, who really care about you.

“That’s what impacted me the most — that there are people looking out for me, people who care.”

Cardentey-Uranga graduated from UNMC with a bachelor’s degree in medical imaging and therapeutic science this past May. He will go on to receive a post-baccalaureate certificate in cardiovascular interventional technology through UNMC.

He wrote a thank you letter last May to the people behind the Ferris Scholarship:

I am looking forward to achieving my career goal at UNMC and hopefully someday to be in your shoes and give back to the community in the same way you are doing with me.

He also created a video for the trustees of the O’Malley Trust, telling them his unlikely story and thanking them for their big hand in it.

And promising his story will continue.

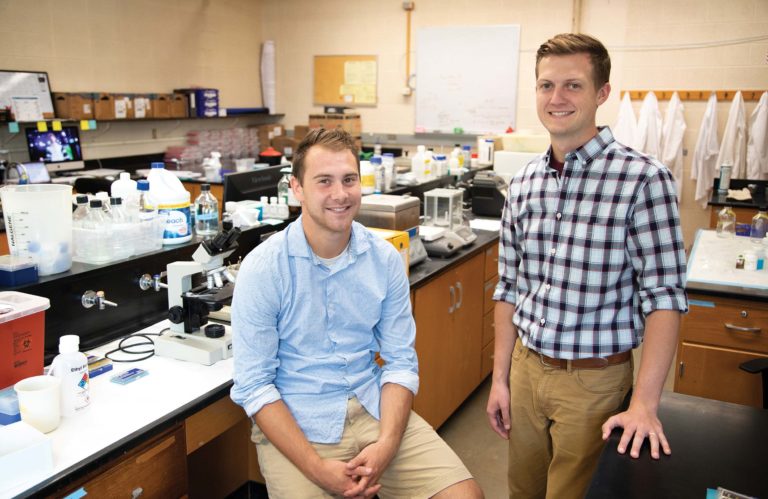

Nik Stevenson runs an experiment for his Master’s thesis about Splenic Marginal Zone Lymphoma (SMZL)/Mature B-cell lymphoma in Allwine Hall at University of Nebraska at Omaha in Omaha, Nebraska, Friday, August 3, 2018.

Home > Archives for October 9, 2019

UNO students make advances in cancer research, discover their career passions along the way.

Jacob Robinson’s dream of being a major league pitcher didn’t pan out. Something better did: He teamed up with fellow University of Nebraska at Omaha biology graduate student Nik Stevenson and together, this past year, made a breakthrough in cancer research — one that could make a major impact in the lives of people around the world who are fighting a rare type of lymphoma. And along the way, the two say, they discovered passions that could make a major impact in their own lives and careers.

They credit the supportive culture at UNO.

Says Robinson: “People here, especially the science faculty, are so willing to help students that I really felt like my education here was great. Because I was willing to put in the effort, people were always willing to provide opportunities for me to go as far as I wanted to go.”

Says Stevenson: “You can fail 10, 20, 100 times, and the faculty here will help you succeed. It’s an environment where you feel confident that even if you fail, you’re ultimately going to succeed, and that’s pretty important to help you flourish.”

The cancer they’re studying is called splenic marginal zone lymphoma, or SMZL. It’s a type of white blood cell cancer that hasn’t been studied a lot because it’s so rare. SMZL cases have an overall survival prognosis after diagnosis of eight to 11 years, so it’s a rather slow-progressing cancer.

But anywhere from 10% to 15% of those cases progress to a much more aggressive form in which the overall survival prognosis drops to three to five years. Their research has shown promise in predicting how aggressive a person’s cancer will be based on specific genetic markers, a breakthrough that could lead to a way to more easily diagnose this cancer.

Stevenson did the “wet bench” side of their research — the hands-on work with the cancer cells themselves. Robinson did the big-data side, studying the genetic profiles of patients with SMZL and looking for patterns for this specific blood cancer vs. other similar lymphomas.

“It’s not a terribly lethal (cancer), unless it transforms,” Robinson says. “What my research did is, I found a grouping of markers that is pretty highly predictive for the basis of diagnosis for this SMZL patient.

“Instead of having to go through a bunch of different tests, ideally you would be able to just have this panel of genetic markers from a biopsy, and you’d say yes or no, this is the lymphoma that they’re afflicted with.”

If patients have the slow-growing type, they wouldn’t have their lives disrupted as much with frequent biopsies, along with the waiting around for results, which can be scary. It also would provide more accurate diagnosis and information on the outcome of the disease’s progression.

Says Stevenson: “It would allow them to pretty much have a better quality of life for the time being.”

People here, especially the science faculty, are so willing to help students that I really felt like my education here was great. Because I was willing to put in the effort, people were always willing to provide opportunities for me to go as far as I wanted to go.

- Jacob Robinson

The two conducted their research in Allwine Hall in the lab of Christine Cutucache, Ph.D., a rock star professor who holds the Dr. George Haddix Community Chair in Science at UNO. They call her “Dr. C.”

Dr. C, they say, gave amazing guidance and support (and coffee and doughnuts and a box overflowing with healthy snacks, which sits in the corner of the lab’s small conference room).

She served as the liaison between them and physicians and other medical professionals at the University of Nebraska Medical Center as they tried to determine the real-world usefulness of their research.

“It’s been sort of the perfect mix to have UNO as a home base but still be able to access a world-renowned med center right down the street,” Robinson says.

UNO, they say, helped them make major breakthroughs in their own lives, too.

Back in high school at Omaha North, Robinson says, he was mainly just interested in baseball, not school work. He struggled in chemistry. His dad connected him with a friend who was a retired UNO chemistry professor, James Wood, who became his tutor.

“He basically showed me how cool chemistry could be,” Robinson says.

That ignited his love for learning. (It also helped, Robinson says, smiling, that he fell in love with a great student his senior year — a young woman who is now his wife.)

At a UNO chemistry department awards night a few years back, Dr. Wood was given an envelope with a name inside. He was asked to open it and announce the chemistry student who’d be named the latest recipient of the James K. and Kathleen Wood Scholarship.

Dr. Wood didn’t know who it’d be.

It was Robinson, then a UNO junior.

Stevenson’s original dream for his career – to be a brain surgeon — also didn’t pan out.

He was a military brat, he says, born in Germany. He lived in Texas and South Dakota. He was only 8 years old and his family was living in Papillion, Nebraska, when his young mother was diagnosed with stage 4 breast cancer.

“It was everywhere when they first saw it,” he says. “It just socks you in the gut when you find out something like that.”

The cancer eventually spread to her brain, and she had brain surgery. Stevenson spent a lot of time in the hospital with her until she died when he was 12. He’d wanted to go to medical school, he says, but not getting in his first try made him reflect on that path, and he realized it wasn’t actually his main interest or career aim.

“That was a blessing in disguise because, through a little reflection, I realized I didn’t want to do that,” Stevenson says.

He met with Dr. C a year before applying to UNO and came to the university for his master’s degree because of the opportunity to join her lab.

Dr. C also runs a community outreach program called NE STEM 4U in which UNO students work to inspire middle school students in the community to consider careers in STEM fields down the road. (STEM is an acronym for science, technology, engineering and mathematics.)

Stevenson loves to coach soccer, too.

“Developing them as people, not just as athletes but just as people who can contribute to society, is a big thing I enjoy,” he says.

Dr. C noticed Stevenson’s strengths as a mentor and connected him to NE STEM 4U. He loved it.

He was its graduate adviser this past year and recently accepted a full-time job at UNO, where he will be doing science education research, continuing his role in the NE STEM 4U program and leading professional development opportunities for undergraduates and others.

“Developing people to excel in science so that one day they may pave the way for great development in the cancer research realm or in a plethora of other STEM fields,” Stevenson says, “is really my passion and my goal.”

He hopes to keep coaching soccer on the side.

This August, Robinson will start pharmacy school at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.

Stevenson thinks he’ll stay in Nebraska.

“My fiancée is a farm girl from southeast Nebraska,” he says, “so I think we’re going to end up calling somewhere around Nebraska home.”

Stevenson smiles.

“Nebraska is pretty good.”